Currently not on view

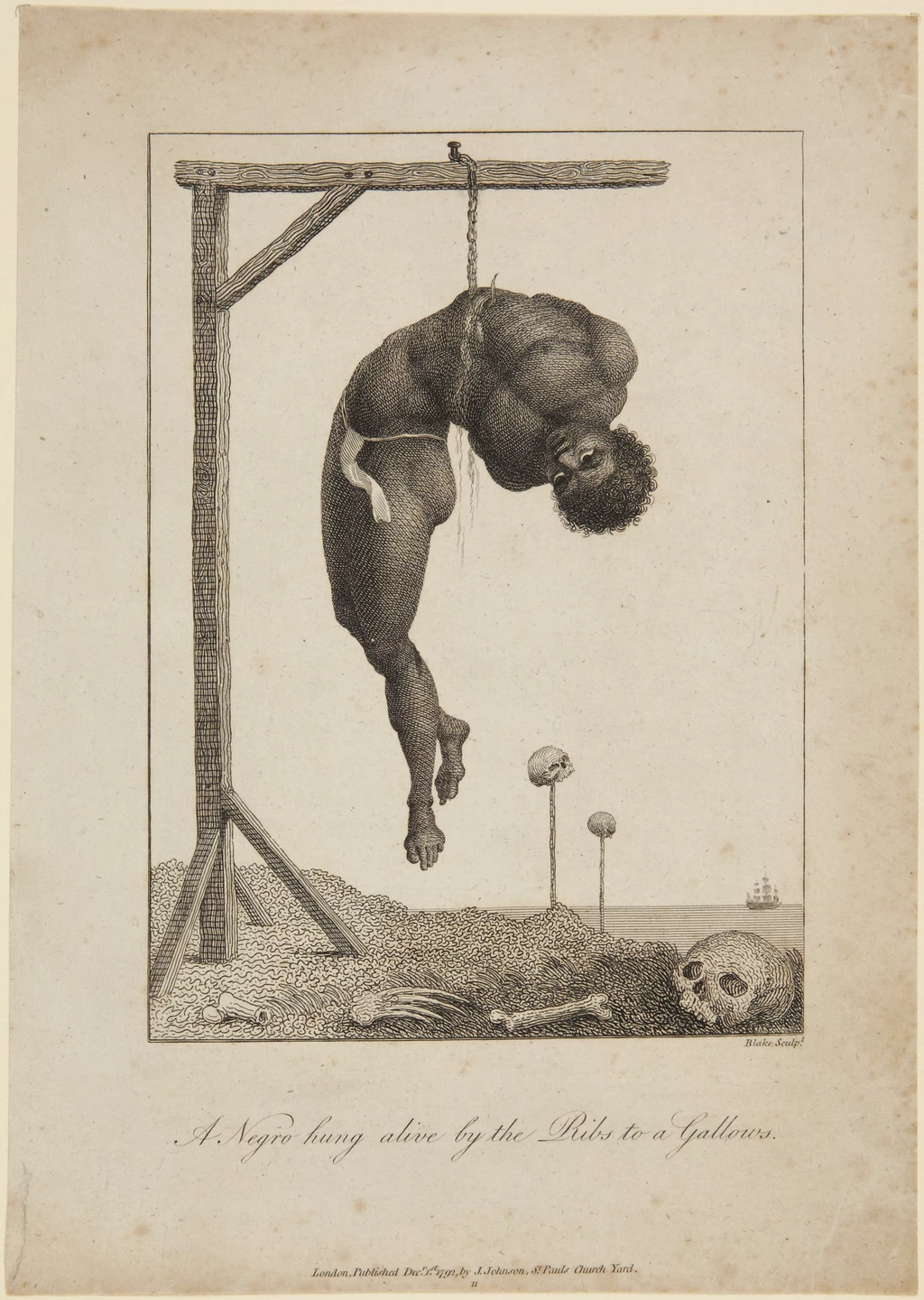

A Negro hung alive by the Ribs to a Gallows, plate 2 from the book Narrative of a Five Year's Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam in Guina ... from the year 1772 to 1777 by Captain J.G. Stedman,

printed December 1, 1792

Published by Joseph Johnson, British, 1738–1809

More Context

Course Content

<p><strong>Student label, AAS 349 / ART 364, Seeing to Remember: Representing Slavery Across the Black Atlantic, Spring 2017:</strong> </p> <p>This engraving by the radical British artist William Blake (1757–1827) is based on a sketch by the Scottish-Dutch soldier John Gabriel Stedman. It comes from a series of engravings that appeared in Stedman’s Narrative of a Five Years Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, which is set within the Dutch capture of the British colony of Suriname during the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1667). After Suriname was overtaken, the major form of resistance became “maroonage,” a strategy in which fugitive enslaved people, or “maroons,” escaped inland to form communities from which they waged a campaign of guerrilla warfare against the Dutch. Stedman himself witnessed the cruel oppression of those enslaved during a campaign against the maroons in 1774. The book was espoused by abolitionists, although Stedman probably supported reform rather than abolition.</p> <p>This engraving depicts an enslaved black man hung alive to a gallows by a single hook through his ribs, a gruesome scene that Stedman recounted from his experience. The brutalized body, along with the skulls and bones on the shore and the haunting ship on the horizon, demonstrate that enslaved lives were dictated by the violent domination of white people over black bodies. Read about another engraving from this series <a href="#">here</a>.</p> <p><strong>Matthew Choi Taitano<br>Princeton Class of 2018</strong></p>

Campus Voices

<p>Blake used momento mori, artistic or symbolic reminders of mortality, to capture the different stages of death that the black body experienced under slavery. First, the skull and three bones spread out across the shore, along with the two skulls propped on sticks further out, remind us of the deaths of enslaved people in the past. Second, the brutalized body of the black man hung alive reminds us of the ongoing violence against and murder of enslaved people during that period. Finally, the haunting ship visible on the horizon symbolizes the brutal future and deaths many enslaved people would eventually experience. In turn, these various symbolic reminders of death help the overall piece demonstrate that the stages of enslaved people’s lives were dictated by the violent domination of white people over black bodies. </p> <p><strong>Matthew Choi Taitano<br>Princeton Class of 2018<br></strong></p>

Information

printed December 1, 1792

John Linnell (1792-1882); Frank Jewett Mather, Jr. (1868-1953)

Share your feedback with us

The Museum regularly researches its objects and their collecting histories, updating its records to reflect new information. We also strive to catalogue works of art using language that is consistent with how people, subjects, artists, and cultures describe themselves. As this effort is ongoing, the Museum’s records may be incomplete or contain terms that are no longer acceptable. We welcome your feedback, questions, and additional information that you feel may be useful to us. Email us at collectionsinfo@princeton.edu.