Currently not on view

Kandinsky and Erma Bossi

More Context

Handbook Entry

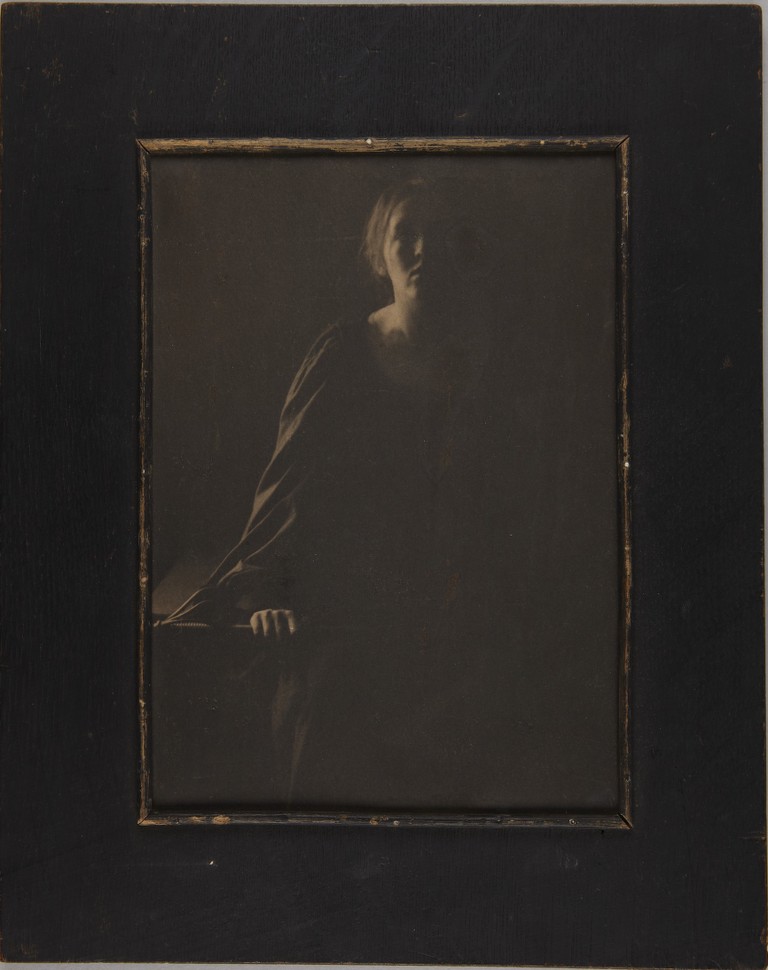

The early deaths of her parents left Gabriele Münter with the freedom and the means to live as she pleased at the age of twenty-two. After a year in Düsseldorf at the women’s counterpart to the all-male Art Academy and two years with relatives in the United States, she settled in Munich. In 1902 she entered the progressive, coeducational Phalanx School, where she studied still-life painting with the Russian expatriate Wassily Kandinsky and attended his summer classes in landscape painting in the Bavarian countryside. Although he had a wife in Russia, they entered into a relationship and lived as man and wife until the outbreak of World War I. During their travels, a stay in France (1906–7) coincided with the exhibitions of the Fauve artists, and the brightly colored works and simplified forms of Maurice Denis, Henri Matisse, and André Derain became important influences for them. After their return to Munich, Münter purchased a house in the Bavarian village of Murnau that became a meeting place for the couple’s friends. This painting and a similar one in Munich show a seated Kandinsky taking tea or coffee with one of the women artists from their circle, Erma Bossi. Kandinsky seems to hold forth, while Bossi leans forward to listen to what must be a vehement statement — he raises his hand to make a point. With Kandinsky’s encouragement, Münter painted some of her most important works in this period, and his role as a mentor seems to be reflected in this image of him lecturing to a woman artist. The generalized forms and block-like colors may be related to Kandinsky’s growing abstraction in his landscapes, but Münter always retained her own figurative style and never followed Kandinsky into abstracted, musically inspired forms. She found inspiration instead in the regional folk art, especially reverse painting on glass, and in children’s drawings. Although Münter and Kandinsky were divided by the war, his return to Russia and remarriage to a second Russian wife, and an eventual bitter parting, Münter’s art always retained some of the lessons of her teacher and lover, interpreted in the light of her own particular genius.

Information

1910

<p> Gabriele Münter [1]; <p> Possibly transferred by her to Lehnbachgalerie, Munich, Germany, ca. 1957. </p> <p> Private collection by 1967. [2] </p> <p> Anonymous gift to Princeton University Art Museum, 2012. </p> <p> Notes: </p> <p> [1] According to Galerie Valentien, Stuttgart, Münter probably hid the painting in her home until at least 1945 </p> <p> [2] Gabriele Münter: Gedächtnisausstellung zum 90. Geburtstag, Heidelberg Kunstverein, 1967. </p> </p>

Anne Mochon, <em>Gabriele Münter: between Munich and Murnau</em>, (Cambridge, MA: Published for the Busch-Reisinger Museum, Harvard University, 1980)., p. 41, cat. no. 37 (illus.)

5136 1980Jill Guthrie, ed., <em>In celebration: works of art from the Collections of Princeton Alumni and Friends of The Art Museum, Princeton University, </em>(Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Art Museum, 1997)., p. 270, fig. 234

852 1997"Acquisitions of the Princeton University Art Museum 2012," <em>Record of the Princeton University Art Museum</em> 71/72 (2012-13): p. 105-132., p. 119 (illus.)

2988 2012<em>Princeton University Art Museum: Handbook of the Collections </em>(Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Art Museum, 2013), p. 222

1994 2013